Snuggling up with my children and a good picture book was one of my favorite things to do when my son and daughter were young. As parents, we intuitively know the value of this intimate exchange, and understand that reading to our children helps them internalize the structure of language and develop their appreciation for the power and beauty of the written word.

How many of us, though, think to “read” the illustrations in a book with the same amount of attention and care that we read the words? And why might this be important?

On a daily basis we are presented with a steady stream of advertisements, signs and symbols designed to shape our decisions and direct our attention. In addition, one look at the Internet makes it obvious that we are becoming an increasingly visual society. If we want our children to be intelligent and discerning consumers of visual information, we need to teach them how to read visual compositions for meaning.

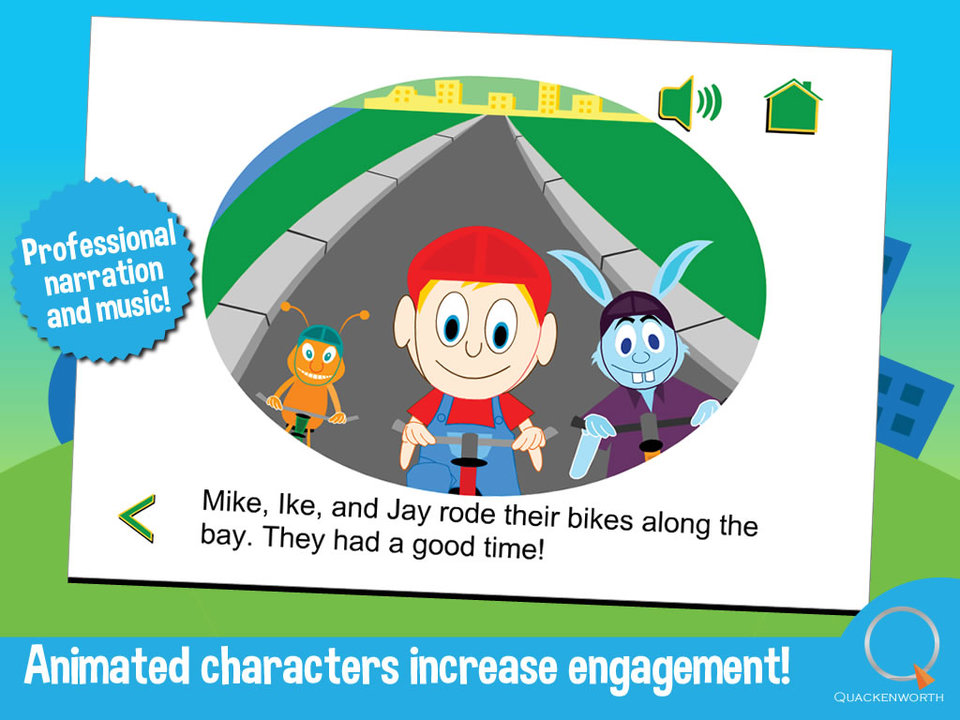

Picture books present a perfect opportunity for parents to introduce their children to the language of visual composition and its power to inform. Illustrators and writers work closely together to tell stories. Thus, when reading the text, it is well worth taking the time to carefully examine what the images have to say. Liz, a parent of two elementary school-aged children, describes how she encourages her kids to explore images in books: “We take ‘walks’ with our eyes through the illustrations of a new book before reading the words. My kids and I have fun together describing what we see, imagining the events of the story and guessing what might happen next when we turn the page.”

Another mom, Diane, uses the illustrations to pique her son’s imagination: “I asked him to tell me the story he saw in a picture. He described himself within the scenes, imaginatively interacting with the characters and participating in the adventure the illustration unfolded. A visual image often became the basis of his pretend play later on.”

Here are more ways to explore illustrations with your child and to help him develop his ability to “read” visual compositions:

Colors

If your child is very young, ask him what colors he notices most in an illustration. Based on what he says, help him connect the color(s) to particular feelings and/or actions. For example, is red describing something exciting, black telling the story of fright, blue something sad, or yellow revealing excitement or happiness? When you read the words, see how they extend or confirm what you “read” in the image. Or, do the opposite—read the words first, then see how the illustrator helps to further the plot with color. An example of a great book that explores the connection between colors and emotions is “Yesterday I Had the Blues” by Jeron Ashford Frame.

Lines

Ask your child to identify different kinds of lines in an illustration and trace her finger along them while describing what the line is doing. A dotted line might be skipping happily across the picture, a thick line plodding clumsily about the page, curly lines laughing, and thin, pointy lines jabbing angrily. Talk together about how the quality and movement of the lines in the illustration match the story that the words are telling. An exciting example of this is the book “Ish” by Peter H. Reynolds, as it incorporates a variety of different lengths and textures of lines.

Shapes and Objects

Engage your child in naming some of the shapes and objects in an illustration and ask him to describe how big those objects are in relation to each other. Help your child see that the bigger the object and the closer it appears to the viewer, the more important it tends to be in the story. Next, ask your child to notice where his eye is initially drawn into the illustration, and to describe the path around the page his eye naturally takes. Notice together if moving in a horizontal path signals that a problem has been resolved; vertical paths indicate ascending steps toward problem resolution, or diagonal paths create anticipation about a solution that is yet to come. Once again, compare how the verbal text matches the visual story structure. Jan Brett incorporates this skill with great consideration and inspires young readers to infer what might happen next in “The Mitten.”

We live in a world where being visually literate is as important as being verbally literate. The more we can help our children understand the language of visual form and how images interact with words to communicate ideas, the better positioned they will be to interpret, understand and engage in the world around them.